Essay in Episodes

After Van Gogh exhibition from Kroller-Moeller Museum in Rome, at the Bonaparte Palace, Autumn 2022 – Spring 2023.

In this essay, I am analysing the works which impressed me the most at the large and representative Van Gogh exhibition from the Kroller-Moeller Museum collection which was tastefully and thoroughly organised at the Bonaparte Palace in Rome from the autumn 2022 through the spring 2023.

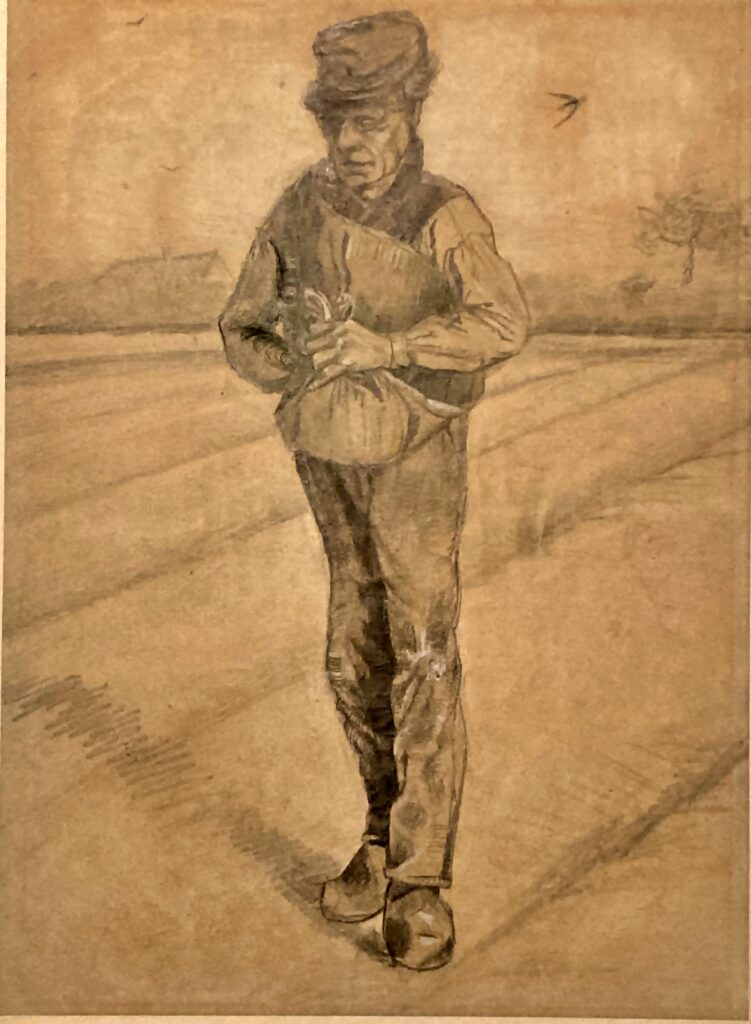

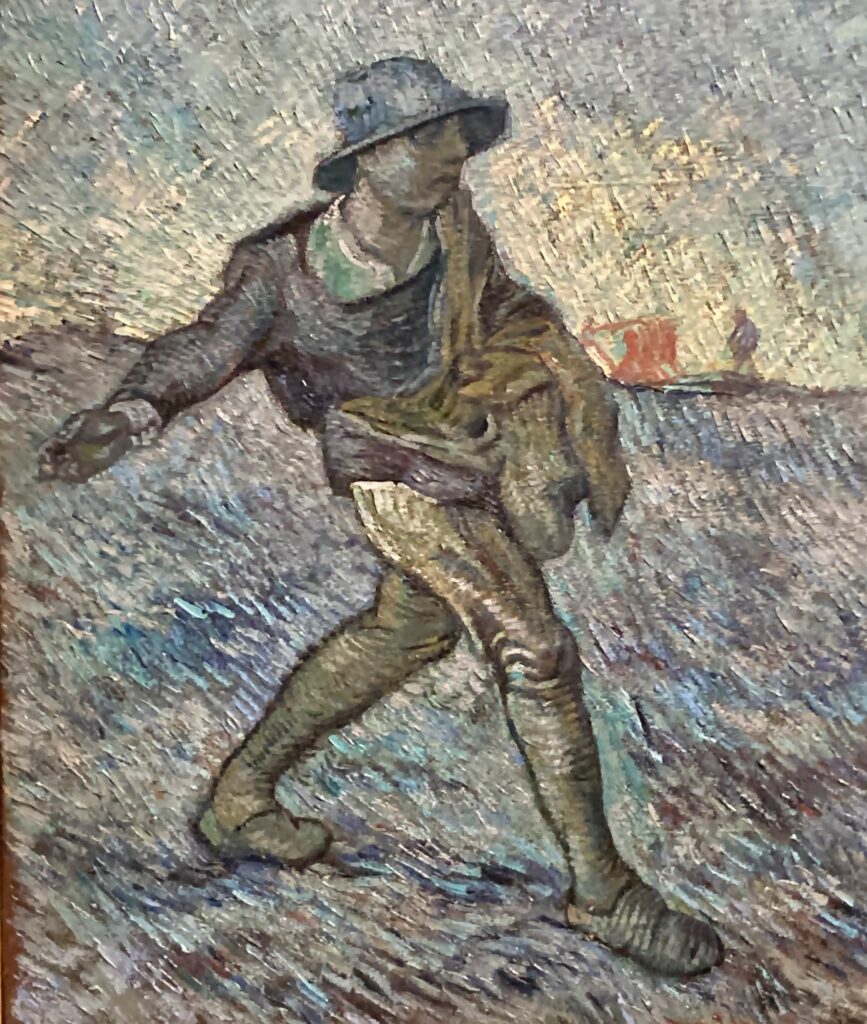

EPISODE One: The SOWER AS VAN GOGH’S SELF-PORTRAIT –

During his life, actually the last decade of it when he was working as an artist full-time, Vincent van Gogh drew and painted over 30 works portraying the sower. For some reason, until this day, accounting a huge amount of research, there has been no mentioning by the art historians in their works regarding an obvious fact that the sower was not just and only a figure conceived by van Gogh because and after Mille images of peasants and their work, but his self-portrait, even a proto-self-portrait. Those three van Gogh Sowers are from ongoing Van Gogh Exhibition from the Kroller-Moeller Museum collection in Rome, Autumn 2022 – Winter 2023

One needs to remember how pivotal for Vincent was biblical symbolism, and how much the meaning of the sower, the function of the sower – whose primary if not sole mission in life is to sow the seeds of everything good and important: knowledge, understanding, kindness, depth of perception, lasting effect of education, and so on meant for the artist. Van Gogh started to paint his self-portraits as the sower yet before he started to make them in a classic way, by rendering his face. Because in his path of understanding of life, the function was always coming first, with analysing the consequences of a function as the following stage of people’s activities in life.

Yes, indeed, van Gogh adored Mille, and not the last because of Mille’s interest in unassuming people and their life. But to see over 30 van Gogh’s Sowers simply as versions of Mille’s peasants is an obvious under-seeing of what van Gogh aimed to tell by and in his Sowers: their principal function, his, Vincent’s own principal function – to sow the seeds of good, to conduct the work of a practical enlightenment, in the way in which a peasant sows wheat which will be processed into the bread, ultimately.

I do believe and see all Vincent’s Sowers as his self-portraits, as self-portraits of his mission in life as he saw it.

Episode Two : THE SECRET OF THE VAN GOGH’S SPEAKING STRAW HAT

Still-life with Straw Hat ( 1881 or 1885)

One amazing detail in van Gogh’s oeuvre is the contrast between his clumsiness of human figures he created, especially in the beginning of his work as an artist, and mastery of subjects in some of his works. If his early works with human figures are placed at an exhibition in the same room with some of his still life works, the immediate impression is that it could be works of different artists, as it happened, for example, at the ongoing Van Gogh exhibition from the Moeller-Kroller Museum collection in Rome.

Extremely mastery van Gogh’s Still life With Straw Hat is an indisputable gem of the first hall of the large exhibition. For some reason, this great work is not exhibited very often. And it is a special pleasure to see it live, not in reproduction.

This Still life With Straw Hat is known to van Gogh’s scholars because of Vincent thorough work with detail, and truly fine and accomplished shadows and its balance. There is a disputable dating for the work, one is for 1881 and another is for 1885. Based on comparative studies, and abilities to draw shown by Vincent in the beginning of his only productive decade of 1880-1890, the later date is far more reasonable to apply, in my understanding. Then Vincent, being for two years in Nuenen, worked in peace and was able to make deep works demanding the time and attention.

Still, that great work did not sell, as he hoped so much. Why? Because it was not ‘fashionable’, as his brother Theo wrote to Vincent from Paris. This work, although so well done, ‘was not in style with the current fashion of Impressionists’, explained Theo.

To me, this not-big Vincent still-life with a hat is amazing. Looking at it again and again, and especially alive, I just can’t get it: how on earth did he make this hat almost to talk to us? What is the secret of this work?

My husband answered to me, with his professional understanding of the artist: “ he ( van Gogh) succeeded in it, as with his other great works portraying objects, not people, because he was able, mentally, to spiritualise those objects. He saw this volume before he painted it. Mental predisposition, his inner vision, has created the volume of meaning in the objects that he was creating, indeed, almost as they were speaking. And he was unique in this ability”, – said Michael. He still is.

Episode Three: STILL-LIFE AS A LETTER –

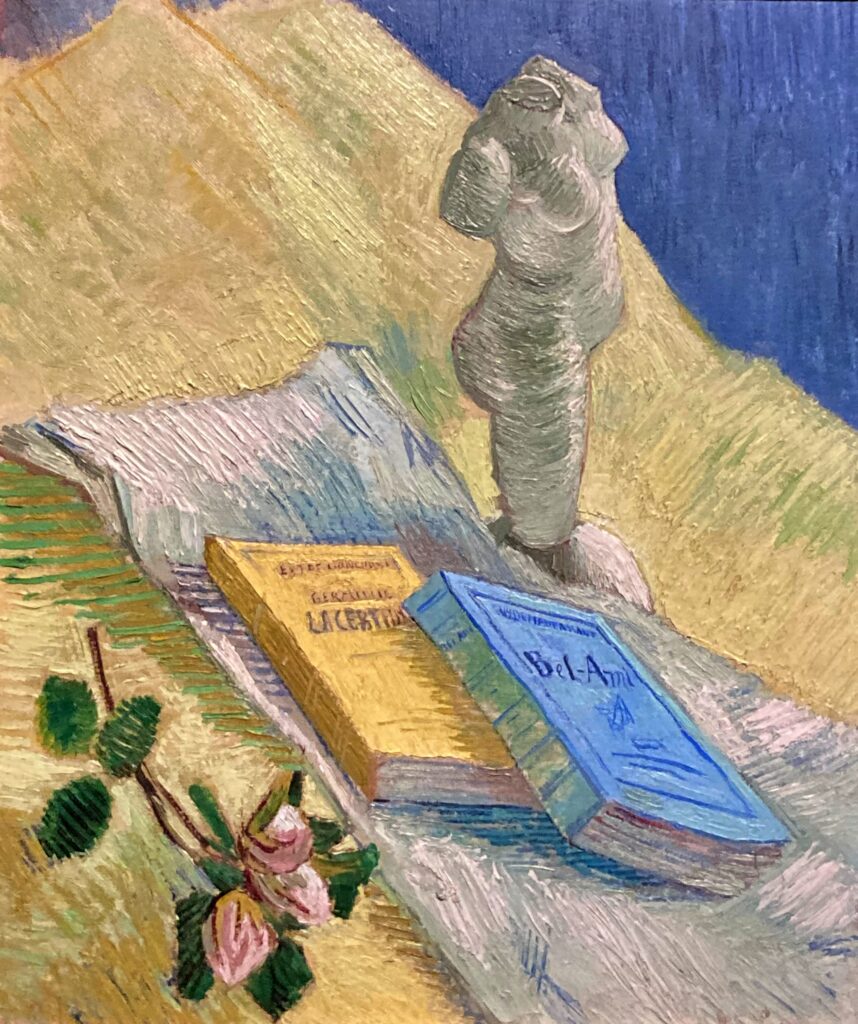

Still Life with Statuette ( 1887)

Van Gogh drew and painted a prevalent number of still life works in his entire oeuvre, with landscapes coming second, and then some genre scenes and portraits. But he was the master of still life first and foremost of all, with landscape mastery coming second in his super-intense effort. And the master in both genres he became because of a deep psychological reason: nature was accommodating, nature did not pose a threat to him, as people were, in his own perception. Being at nature, and working on the objects, not people, made him free. Vincent was a wounded soul, because of a number of reasons, including genetic ones. He was unsure of people, he did not know how to treat them properly. He was a clumsy communicator, and his very sharp and deep mind was in a permanent conflict with how that special brain’s embodiment, the man called Vincent van Gogh, was perceived by practically anyone around him, except Theo, but also with some breaks in that life-line for Vincent, as well although short ones. That’s why the letters. Because Vincent felt absolutely obliged to explain himself, and that’s exactly what he did since his youth, as to Theo, as to anyone else with whom he communicated in this way.

But with objects, who were not people who could wound a vulnerable soul, the genius of Vincent felt itself at home. And we are immensely lucky to inherit these works. As the small still life which is well-known but is not shown internationally often. This masterly Still Life with Statuette was painted by Vincent in 1887, three years before his tragic death.

This work is truly special because it is his letter to Theo in the form of a painting. Its neutral name should not mislead us. Most likely, the name was given to the work at the later stage, after the death of both Vincent and Theo, when it went to the dealers. The circumstances of the creating this very elegant and articulated work were rather sober, and undoubtedly very sad for Vincent. The work was done when Vincent left Paris after two years of living there with his beloved brother, his entire world, actually. Vincent left because Theo was finally engaged to Johanna Bonger, and very sad Vincent realised that he would become a burden and unwelcoming distraction to his brother and his fiancee. So he decided to leave Theo’s Montmartre apartment in Paris which he loved with all his heart, and thus, to leave Paris, which he did not love, and of which he was permanently frightened and nervous about.

The roses are pointing at Theo’s engagement to Johanna, and there is no coincidence either in number of or in disposition of flowers. There are three of them, but two are close to each other, and one is on its own, or left of its own, according to Vincent’s language. And that Venus statuette is not only a lovingly ironic Vincent’s pointing towards the reason for the major change in his brother’s life, but also a fine hint on his not that fruitful couple of years of his drawing classes in Paris where he was painting this model numerous times, without much success though.

With his ever present didactic momentum, Vincent placed two books in his gentle painted farewell letter to his brother. Being methodical as he could when he decided to, Vincent accurately labelled the books. Both are of his and his brother’s beloved authors, tellingly, the Goncourt brothers and Maupassant. Germinie of the Goncourt brothers tells about a double-life of a housekeeper. In his letters, Vincent mentioned that the book ‘describes and tells about life just as it is’. As for Maupassant’s Bel Ami novel, quite popular at the time, both brothers called it ‘a masterpiece’. The main theme of the novel is opportunism as a mode of life.

So, shrewd Vincent painted an elegant farewell letter to his brother, with clear statement and full of symbols understood at the time only to two of them. This kind of treasure, living dialogue on canvas between Vincent and Theo van Gogh, we have a privilege to see 235 years after Vincent painted this saddened but very gentle goodbye to his brother and to Paris.

Episode Four: LANDSCAPE AS A PORTRAIT ‘OF FINE MELANCHOLY’ , or HUMANISING THE CONCEPT OF A RAVINE – The RAVINE by Vincent van Gogh

“It was a desperate period in Vincent van Gogh’s life. He was very, irreversibly sick, even crushed, mentally. He was in an asylum. An asylum in which he came in voluntarily. He has decided to come to an asylum, it was his own decision, his wish, his conscious choice – not quite a common deed for mentally ill person, one has to admit. He has placed himself in a capsule which he hoped would heal him somehow, with time, but most and foremost of all, it would protect him. Because protection was the thing he missed in life the most. All his life. It is perhaps that overwhelming vulnerability of Vincent which made his genius so tangible and so unparalleled up to this day. The vulnerability from which he instinctively tried and haplessly could not find any shelter. This futile, tragic search is basically the story of his life.

It had been ten months, almost a year, since the time of the terrible incident with his uncontrollable rage and cutting his ear off occurred. It happened on the Christmas eve of the previous year, 1888, and that rage episode has broken his friendship with Paul Gaugin, which Vincent was building with such effort and awe, unlike Gaugin who was rather on the receiving end, so to say.

During ten months after the hysterical scenes in Arles and Gaugin’s immediate departure to Paris in a horror, in an understandable fear of his uncontrollable friend Vincent, the waters calmed down between the two of them. Being in safety and far from Vincent’s rage attacks, Gaugin with whom Theo spoke for length and did his very best to amend the damages caused by his poor brother in all possible ways, including very practical ones, became to treat Vincent with a positive twist, from a safe distance.

At the same time, spending his time at the Saint-Paul asylum near Saint-Remy-de-Provence, Vincent kept his long walks in the picturesque areas around it. And Vincent’s long walks meant an extraordinary length indeed. He always had that intense accord between his wish to see the world and his physical ability for strenuous exercise. It is like he was testing himself non-stop, and he liked the process of overcoming. He also proved himself, once and again, also in this.

The place which he painted in an unusual way lies in a practically unpopulated area. At the time of Vincent visiting it and walking around, just 395 people lived there, with 250 inhabitants living at the Peyrolets today, as I was interested to establish. It is a very stony place, green as one expects it to be in Provence, but quite stony. And those stones grabbed Vincent’s attention firmly when he was walking around there one hundred and thirty three years ago.

I do not know if he knew anything about the etymology of the picturesque place’s name. He was an avid reader, and his mind was sponge-like, so he might have heard or read that the etymology of Les Peirolets goes back not only to ‘a stony place’, but might also mean ‘a ruin’. Just wondering.

Vincent’s view of the mountains in Les Peirolets is stunning. It is stunning as such, and it is yet more stunning when and if one would compare is with the original, natural view of the place of that ravine which grabbed his attention so very powerfully.

Of course, seeing in October, the environment of stony landscapes are not that freshly green as in summer, even in Provence. But still, it is never that grey and that stony-like, as in van Gogh’s amazing work, intense, beautiful, inviting and conceptual.

He never gave it the name under which it is known to us, Ravine in the Peyrolles. He called his work precisely as he meant: The Ravine. And although he worked from a nature, as he prevalently did, out of his principle, he exemplified the stone-like characteristic of that ravine. The Ravine.

To paint at that place was somewhat challenging for Vincent, as we know from his letters to his friend artist Emile Bernard. During the time of his work on The Ravine, in October 1889, Vincent wrote to Emile about ‘fine melancholy’ of the places he is walking through in his long walks, and about his excitement to work ‘in a rather wild place’, at the ravine of Les Peirolets.

He also experimented in this work. On the canvas which is of a decent size , 72 x 92 cm, Vincent for some reason, left many places unpainted at all. He did it so organically and masterly that if one does not know about it, one would not notice. On the contrary, one would notice an amplified volume in this magical work – and that extra-volume was achieved precisely because Vincent left many places untouched thus making the contrast with the painted in gusto nearby spots super-volumized. He was proud about his craft achievement, but Theo was not, and he dressed his brother down with a cold shower in his letter calling the technique ‘too artificial and not impressive’. Theo was rarely wrong about art, but interestingly enough, most of his art expertise mistakes were made regarding Vincent’s works. It happens, in a family.

Despite Theo’s discouragement, when the work reached Paris where Vincent did send it, it was no one else, but Gaugin who became enthusiastic about this work. So much Paul Gaugin, a tough master himself, did like The Ravine that it was the one of the works which he immediately traded with Vincent for one of his own masterpieces, as was the practice between friendly colleagues artists at the time, and as it was going on in a vivid motion between Gaugin and van Gogh.

Interestingly enough, in his conversation with Theo, Paul Gaugin called this very work ‘beautiful and grandiose’ – I can imagine how Theo was puzzled, after his cold shower over Vincent’s shoulder about this very work. More, in his letter to Vincent Gaugin went on, meaning that very painting: “In subjects from nature, you are the only one who thinks’. It is hard to overestimate what those words coming from Paris, from such indisputable master as Gaugin , after all quazi-turmoil that occurred between the two men just about less than a year before, meant for Vincent walking tirelessly and against all odds among the stones miles away from Saint- Remy.

We know that Gaugin who received The Ravine painting from Theo soon after Vincent sent it to Paris, did care about it – as he did about all Vincent’s works which he got from van Gogh, on his own wish and choice, in their mutual exchange. We know about it because he took special care of storing all Vincent’s works in his possession with Theo’s widow Johanna, when coming to his next Tahiti trip in the spring 1891, soon after he got The Ravine. As he would never recover any of Vincent’s paintings belonging to him, due to the misfortunate maze of his own life, the great works saved by Jo eventually found their way to their current place, at the Kroller-Moeller Museum.

The Ravine is a masterpiece because of many reasons: its intensity, its composition, its perfect proportions which are hyperboles but still are perfect, its coloristic which is harmonious and striking at the same time, those inventive red spots about which Vincent was quite proud of, very justly, and yes, his inventive non-painted spots all over the work which gave it an extra-volume. But to me, the magnet of this very special work of van Gogh are those two female figures in the very centre of it.

Moving through the ravine, they humanise not only the stony landscape which is a telling metaphor by the artist about the hardship of life, or rather a life as a journey through hardship, but those two moving female figures in red among the prevailing greyish and stony landscape around, they humanise the very concept of The Ravine. And I just love it.

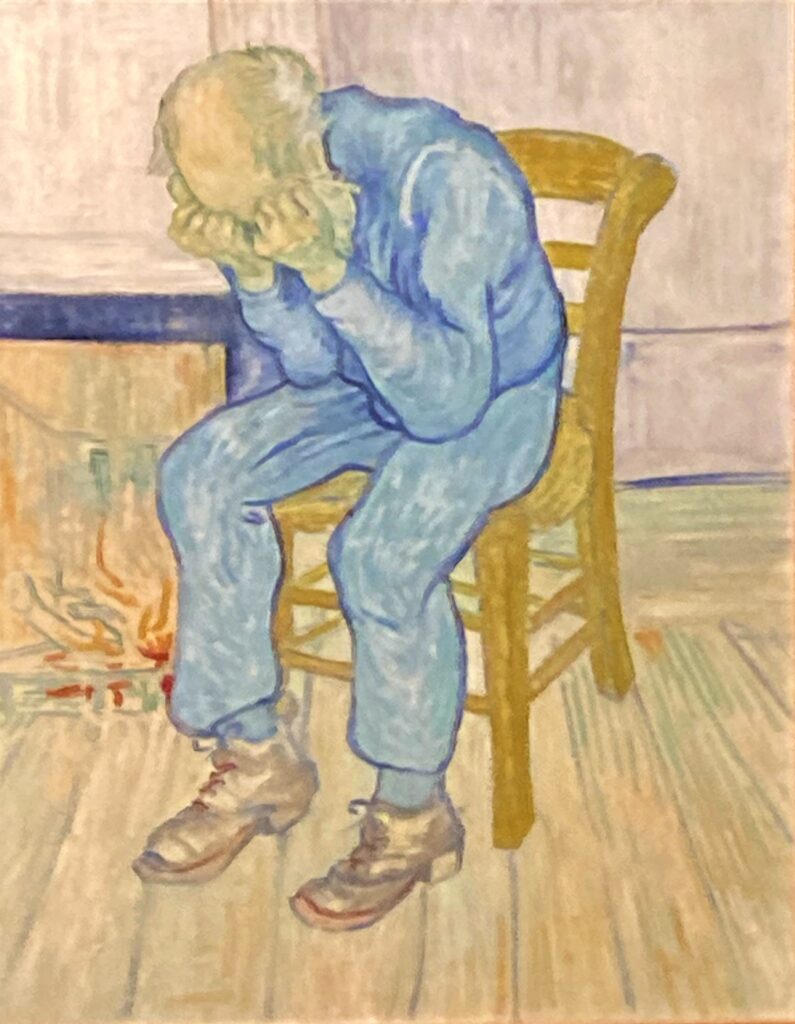

Episode Five: Transformation of Paradox of Hope in Art: From Enlightened Darkness of Rembrandt to a Pastel-Colourised Reality of Vermeer in Fragility of van Gogh: Worn Out ( 1882) and At Eternity Gate ( 1890) artworks

This image is quite well-known in van Gogh’s oeuvre: an elderly man in despair. Depending on one’s own age, and degree of knowledge, one can interpret this classical image in various ways assuming almost equally justifiably that in those works, there are several of them depicting the same image, van Gogh expressed his vision of despair due to poverty, or illness of the person, or illness or death in the family. It could well be also the despair caused by the old man’s age, his helplessness because of it, or his thoughts of his closing time, so to say. Or the person drowned by van Gogh could be just tired, especially on the earliest of all seven known depictions of this very same person. The person was real, a 72-year old army veteran Adriannus Jacobus Zuyderland, who did appear as a model for Vincent in many of his works during his period in the Hague and who was later identified by one of the art historians.

Adriannus lived along with other same age army veterans in one of the houses for elderly in the Hague. Vincent, who had a good heart and relied on people with empathy, called those people ‘Orphan Men’.

We know about seven van Gogh’s artworks depicted Mr Zuyderland in that pose of despair: one drawing, one lithograph which he made of that very drawing being very happy of the result, two watercolours, one oil painting, one work which was lost, and one more which was miraculously resurfaced as recently as in 2021.

Two almost identical drawings and one lithograph were created by Vincent in 1882 in the Hague, and one could clearly see his struggle with drawing a human figure in these works. That struggle is not of a surprise to anyone who researches van Gogh. These works are known under the title Worn Out in English which Vincent himself gave to the work in his letters to both Theo and his then friend and mentor artist Anthon van Rappard. That English title originated many leads to the inspiration of the work, some of which are not substantial. Knowing van Gogh’s immense interest towards Charles Dickens, and the books published with the illustrations for Dickens stories at the time, the source of the original Vincent’s inspiration for his Worn Out man comes from there. But as always with van Gogh, an impulse for anything he did, is only a part of the story. It’s ignition. The rest and the volumised outcome bursts out by the complicated, oversized, disorganised personality of Vincent, and the way of his procession of the material life around provided him for his works which know no boundaries.

I am interested here in two other Orphan Men in Despair which both are far from the original image in Vincent’s drawings of 1882, and the evolution of that image in van Gogh’s inner world and his own thoughts. Moreover, I am interested in understanding the evolution of a paradox which emanates from these two works. The paradox of hope. Because in Vincent’s world, a hope which was a constant despite his recurrent depressions, was always a paradox, due to those depressions, among the other factors, in that weird circle which had no beginning and no end. Or had it?

Unlikely van Gogh’s Worn Out drawings and lithograph of his Orphan Man, his other two works depicting the same person in different techniques and with a distance of eight years, which is a huge difference given that Vincent worked as an artist for ten years only, are very good, extremely expressive and very interesting. They also are very different, with Rembrandt influences first watercolour done in 1882 and van Gogh’s own palette but the one very close to Vermeer’s one oil painting created just two months literally before his death.

In a rare case in art, we are able to follow the evolution of one idea by the same artist depicting the same model and the same subject. It is a rare treat of art, indeed.

In the darkish, badly damaged watercolour known as Sorrowful Ol Man ( created by van Gogh between November and early December in 1882) we are seeing a very good pupil of Rembrandt whom van Gogh, as many best artists throughout the history of art, including Chagall simply adored, and very justly so. Rembrandt is an epoch of its own, not in the arts only, but in philosophy, psychology, mentality, and perception. In ability to see, to perceive, to process and to depict. Rembrandt is the unique phenomena in our civilisation, of the similar character as Mozart is. It is genius in its pure and concentrated form. You cannot re-do Rembrandt as you cannot re-do Mozart. You can only study both to widen your own horizon and to be grateful for the existence of such a vision and such art which is comparable to an element of nature. But we would never get how on earth either of them produced what they did. One can understand, after thorough multi-years studies, how Michelangelo did what he did. But not necessarily one can get how Donatello achieved those genius sculptures of his.

Van Gogh, being from a devoted family, did not get the image of his Worn Out man only because it was a popular motif in a widely read book. Rather, the theme of a human sorrow – and thoughtfulness with this regard – jumped into his kind heart naturally. He felt for his Orphan Men. He was interested in human conditions, and sorrow was probably the first one for him to examine it artistically, judging from the dating of his works on the theme. He thought graphically about people in sorrow ( there are two drawings of women in sorrow as well, from the same period) in the third year of his immersion into the profession of an artist.

The watercolour Sorrowful Old Man is striking. Not only is it very honest. There is hardly a more honest artist among them all than Vincent van Gogh. But it bears Rembrandt’s essential idea of hope as the enlightenment of darkness in a metaphorical way and meaning. It is done under clear and mighty influence of Rembrandt but it is not just a copy of Rembrandt in any way. It is van Gogh’s own very successfully and masterly done dynamic of sorrow which is surprising for his craft at that stage of his artist’s activities. To me, it tells that he fell for his Orphan Men, he was very considering towards a human sorrow in general too, he loved and understood Rembrandt, and all this together came out in this small but piercing, attractive, thoughtful, very memorable work of art, the one of van Gogh’s gems, really. Generally, this great work of his is under-rated, and it is influenced by the fact that it is seriously damaged and cannot be exhibited too often, although it belongs to the permanent collection of the Kroller-Moeller museum.

By 1890, eight years passed from the time when van Gogh created those few Worn Out men of his. In that incredible and unique life, eight years, especially those ones, the last ones of his, are compatible with 40 years of life of many other people. He is in the asylum in St Remy. He has two months to live, but he does not know that. I disagree with the prevailing theory of the van Gogh’s suicide. It was not, in my opinion ( and research). At that stage , he is mostly in bad shape mentally, down to prevalent months of deepening depression. But then, he relapses every now and then, and he sees life in a lighter way. At one of those graceful moments, he remembers one of his successful ( even the lithograph was made of it, he remembers) drawings. Not the drawing was successful, he thinks, but the image, the idea, the message. Vincent was right of it: not only the lithograph was made of it ( he did it himself, but it was successful indeed ), but many of his drawings created in the Hague were sold, actually. When we repeat that only three of his works were sold, all to his friends, we miss out that additionally to that, many of his works were exchanged for very good and valuable artworks of his artist colleagues. And as many as 116 his drawings were bought by a known collector Hidde Nijland as early as back in 1882 after two first exhibitions of van Gogh organised in the Hague by well-known Dutch artist Jan Toorop. This is this extremely worthy and coherent collection of van Gogh early drawings that has become the nucleus of his splendid collection at the Kroller-Moeller museum.

Back to St Remy in May 1890. Vincent is in decent shape, in between the waves of intensifying depression, and he wants to paint. For some reason, he does not want to paint anything new, or from nature, as he loved to do close to that period. His thoughts are coming back to his earlier years, namely to the Hague years, namely to those two of his very first exhibitions. He did not have many of them, anyway, just some efforts, or minor participation – because prevailing at the time Impressionists did not take him neither as one of them – and he was not, not as a colleague, not personally. He had no chance with them – and he knew it. So, he was comfortable and warmed up with his thoughts about home, the Netherlands, and his work and exhibition in the Hague.

And yes, that Orphan Men. How would I do them now? – Vincent thought for himself, and I am not fantasising here, as it is exactly what he wrote to Theo at the time. This is how At the Eternity Gate painting appeared. It is not just a striking painting of a large enough size ( 82 x 65 cm).

It is a heart-piercing poem by Vincent. Why? Because he used favoured by him in the abrupt end of his life not screaming, but beautifully graceful palette of Vermeer , that gentle light blue-light yellow and light beige one, and because he decided to paint the man in sorrow – for whatever reason he is – in beautiful, gentle, soothing colours. It is like playing Chopin in the way the best Polish pianists do – very quietly, in a very fine, not screaming motion. It makes one’s heart stop, almost.

And unlikely as in previous compositions of the same theme, the fireplace in the oil rendition of the Sorrowful Man is very prominent in this van Gogh’s stunning work-song. If in two ( out of seven) of his Worn Out works, the fire-place is just depicted more or less schematically, in this oil work, it lives. And it becomes the counterpoint to the entire work, and changes its message effectively. There are two more customary late van Gogh’s elements in the work: that immortal chair as a metaphor of a person’s connection to his place whatever that place is, and those shoes which has also an important metaphorical meaning for van Gogh personally expressing the belonging of the persons he depicts in those shoes, or shoes on their own as a mirror of his own financial situation. We know that when he died, his shoes were unpaired ones. And he actually cared about it – as anyone would.

All those important for Vincent symbolic components are painted very well and very tangible in this light-blue song of a human sorrow in his At the Eternity Gate: the shoes, the chair, and the fireplace. The man too. And the idea that we do not see the man’s face at the Eternity Gate is both merciful and delicate , as van Gogh was himself. It is also inventive and efficient artistically – because it makes everyone looking at this painting think.

Think about what? Van Gogh gives us the best possible answer to this question in his letters. In the beginning of his artistic career, at the time when he started to draw those Orphan Man, he recognised that he cannot put his ideas on paper or canvas well enough. He wrote: “ I cannot say it as beautifully as it is in reality. I can say it only as seeing a reflection in a dim mirror” – and this is exactly what we saw in the Sorrowful Old Man, a reflection of human emotional life as a reflection in a dim mirror. Eight years on, Vincent painted beautifully the thoughts which were with him all the time regarding this period in human life when people started to think about eternity. Two months before his untimely and tragic death, he painted the work about ‘something precious, something noble that cannot be meant for worms’, in his own words.

This transformation of a paradox of hope seen in two van Gogh works depicting the same man and the same idea in two different techniques in a period of eight years between the works, is amazing. It makes the journey from enlightened darkness of Rembrandt to pastel-coloured world of Vermeer being at the same time so distinctly van Gogh, showing the beauty and extreme fragility of his own naked soul, his own world, striving to the goodness and kindness and never finding it in his own life.

Episode Six : FAIRY-TALES CREATED BY LOOKING FROM BEHIND THE IRON-BARRED WINDOW: Two van Gogh Wheat Field Landscapes

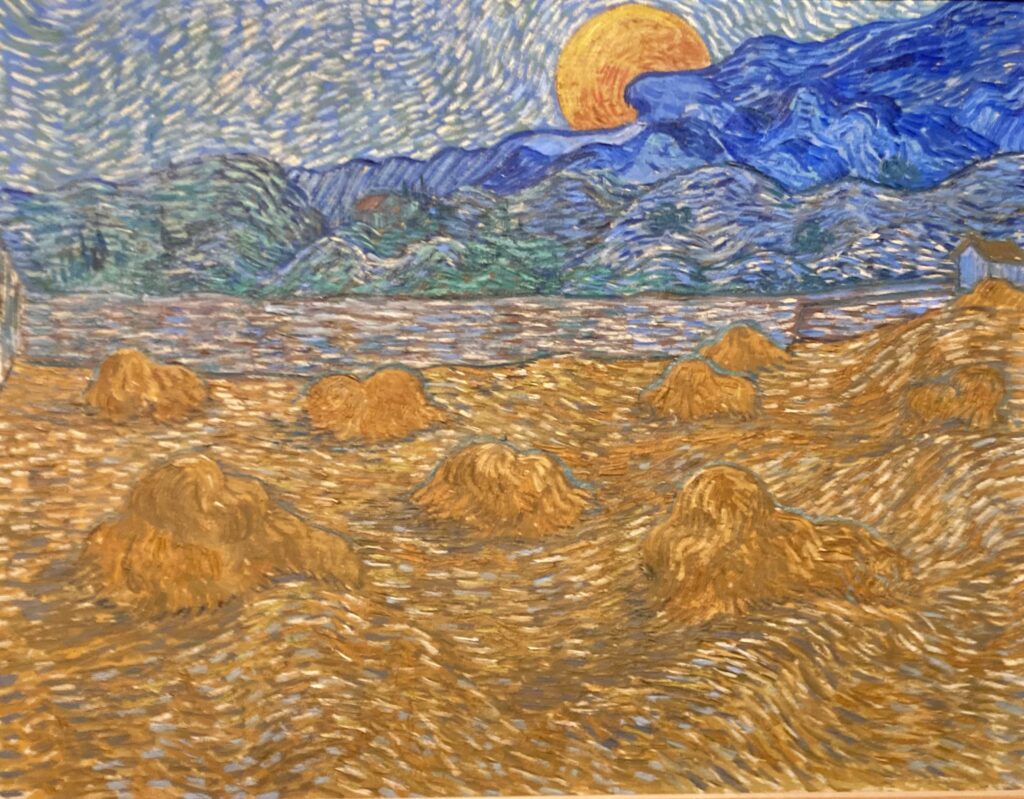

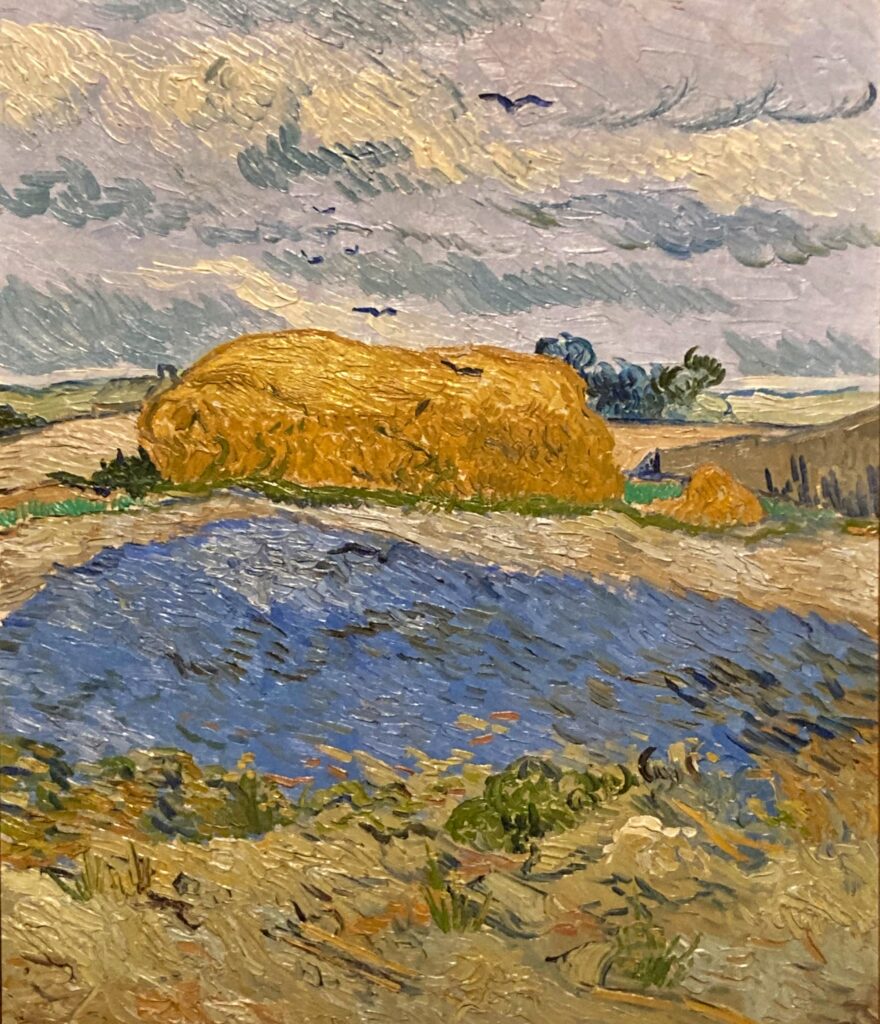

Landscape with Wheat Sheaves and Rising Moon ( 72 x 92 cm, July 1889) & Wheat Stack Under Clouded Sky ( 63 x 53 cm, July 1890)

We know those pictures. We saw them many times. Their subject is so similar that it almost got into our sub-consciousness as one, those van Gogh pictures of wheat. There is a series of them, a dozen, of those modifications of wheat, in different seasons and under different weather conditions, but always painted as seeing from the same spot.

The two of them I saw recently afresh, live. Although their plot is very simple, just a part of a wheat field, they are magnetic, as most of van Gogh’s works are. And the magic of the art seeing as it should be, live, is that it gives you something new every single time you are watching it.

I have a large library of art catalogues and albums, including catalogues raisonne because if you are serious about an artist you would not do without it. But all my long experience as an art professional made me positive that if you did not see a certain work live, you have not seen it at all.

The both works picturing van Gogh wheat stacks were created by him in the period of an exact year in between them, both were made in two last Julies of his life, the Landscape with Rising Moon in July 1889, a year before his death, and the Landscape with Clouded Sky in July 1890, in his last month.

Both works are intense and magnetic, and these signature for van Gogh and his landscapes qualities are present there in a full measure: the earlier landscape with a rising moon which is completely identical to sun in van Gogh’s perception, on purpose, is masterly balanced in composition, very articulated in its coloristics, and absolutely artistic in its imagination, transforming a basic landscape of a wheat field into a cosmic fantasy picture.

Van Gogh had his special attitude and understanding towards sun and moon, and he was quite serious in almost identifying them. For an artist, it always is a fruitful game. But he did it being prompted by his thoughts, and his thoughts of an extremely well-read person were most of the time based on his knowledge or his reading. Vincent knew both Testaments very thoroughly, and he also was very versed in theological and theo-philosophical literature. In this literature, there are many mentionings of the commentaries to the Old Testament which states that according to many interpretations of the Creation, the sun and the moon at the time of their creation initially were of the same size. I am leaving the subject’s further development here, because I can see from most of the van Gogh’s works depicting both sun and moon that he saw them of an equal size, and that this disposition of a possible original equality , even in a size, but perhaps, in some other characteristics, of sun and moon , some of their functions, some of their influence, and certainly of their both’ enigmas, occupied Vincent’s artistic essence to a very large degree. It truly is tempting to imagine a moon equal to the sun, not only in size, but also in its colour, and its intensity, its message, and its impact on everything around it – as we see it in this beautiful landscape with a rising moon.

Rising moon is never of a colour of which Vincent painted it on his landscape a year before he died. And it never appears closer to the horizon, in its move up from the line of a horizon, certainly not in Provence. Vincent painted a fairy-tale, equalling the moon with the sun in that painting, in all its characteristics: colour, size, location and movement. He was entertaining himself. He needed it. He needed some fairy-tales in his life closer to its end.

The later landscape, painted by van Gogh in a year’s time, very close to his death, is obviously bleak, and it is not as well done technically as the one portraying the same place a year earlier. Even if one would not know or pay attention to the dating, one can unmistakably see that this landscape with Clouded Sky is cheerless and is done artistically rather roughly. I would say that it was done by an artist who did not actually care about what he was doing, did not brother much. Still the wheat stack there with its intense colour bears Vincent’s message. And those birds which are never are joyful or care-free signs on van Gogh’s canvases. His birds – which in his perception often were symbolising souls , in direct tradition with theological philosophy – are always signs of his distress, worries, emotions, and reminding of an emotional turbulence, in a compassionate way.

So, what’s the reason for that series of van Gogh wheat stacks? Did he have a special attachment to wheat, of all plant species? He did not. He actually found them ‘rather dull’ as it comes from his letters to Theo. And they well might be. He did feel a special attachment to a field as a philosophical concept. And on this philosophical concept is actually based van Gogh’s so strong and long-lasting affection for Millet. Not on Millet’s draughtsmanship, not on Millet’s subject matters, but on two things: Millet’s approach to art, and Millet’s creative exploration of philosophical concepts. Vincent van Gogh had a brilliant, paradoxical, inquiring mind, and his art, especially in its origin, was an initially artistically clumsy powerful processing of his intellectual quests – which were never clumsy. Field as a concept was a constant magnet for van Gogh, as there were other important for him concepts: his speaking trees, his defining skies, his hurdling mountains, his life-conditioning waters in all its shapes, and his exaggerated joy in flowers, flowering joy, so to say.

The two landscapes that I am referring to are not dull at all, despite Vincent’s own mentioning of ‘rather dull ochre-yellow and violet colour’ in describing the work to Theo in his letter, prior to sending it to his brother to Paris.

Sending where from? From St Remy de Provence, a beautiful place, indeed, – if one is not confined into one’s small room in an asylum, as Vincent was at the time. His room at that period in the asylum in St Remy, was of the type of real confinement, the one from which a person would not be able to run away. It was a very small room on the top floor of St Remy psychiatric clinic, in the far corner of it. Above Vincent there was only the asylum’s roof, not even a wall next to his small window there.

Ah, and that window. That window. Where from Vincent was watching hungrily as a wounded bird all the time, at any season, any weather, any time of day or night. His sight was reaching for as long as the small window allowed it. We know it from his letters, many of them. That’s why we have inherited a dozen-plus series of that certain small spot of a wheat field, from the same point of view. That’s why Vincent had to examine artistically that dullest then dull for him, under the circumstances wheat set in all seasons and in all stages of a physiological process of a plant life: reaped, under rain, in stacks, under the sun-moon, or moon-sun, who actually cares, with some birds or without them.

And then, there is one, last, but actually the first pre-condition of creation by Vincent van Gogh of those landscapes from the now world-famous wheat-field series. The iron bars which were set firmly in his very small window in his very small room at the St Remy asylum isolating him from the world. So, the unparalleled genius of art was doomed to observe the patch of the world which was available for his observation from behind and through those thick, heavy, ugly and actually threatening , such is a function of and characteristic of metal in our life, black bars of iron which commanded his view during that last year of his unhappy life.

One needs to be Vincent van Gogh to leave us those intense, beautiful, mesmerising landscapes he created seeing the framed spot of space in front of him from behind those black iron bars.